Textiles were precious in the ancient world. We have echos from this in the Bible and in the Scottish tartans as well. Not clothes per se, but rather pieces of cloth that could be used as clothes, as bedding, as blankets, and even as positive identification, this is something that connects the ancient Levant to the Scottish Highlands all the way up to the industrial age.

Copyright: David Ball [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

Copyright: Bain News Service photograph. [Public domain]

Joseph’s striped shirt was so precious that his brothers could not resist the temptation to condemn him to a slow death in a desert pit to take possession of it. Mourners were identified by their refusal to wear the everyday cloth that identified their tribes, their status, and even them personally, donning instead the monochromatic and thus non-identifying sack cloth. It was as if they were saying that grief makes equals out of all of us, it deletes our personal, tribal, and social differences and unites us in sorrow. When Yehuda was asked by a woman who he thought to have been a temple prostitute for a piece of ID as collateral for future payment, he gave her his staff, his signet ring, and his “pthil”, a piece of cloth, perhaps with a “wick”, which is the meaning we reserve for that way today.

That wick, a series of knots that ties together a few strands of woven thread, survives to this very day in our prayer shawls. The exact way the knots are tied and their number is what makes a simple flat cloth into an article of religious observance, perhaps one that is most associated with Jews throughout history. But Yehuda, who lived in late Bronze age Canaan, was really not so different from people who live today in Crown Heights, New York, New York, or Ma’ale Adumim, Judea, Israel. All observant Jews wear under their shirts a “talit katan”, a small prayer shawl made into a kind of poncho, with four “tzitziot”, wicks, or one suspects as Yehuda would have called them, “pthilim”.

Copyright: Christopher Michel [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]

The original identifying nature of the “tzitzit”, the wick on the prayer shawl further rings to us across millennia in our burial customs. When I die, my earthly remains will be wrapped in my prayer shawl, but not before its four tzitziot, its fringes, its wicks, its pthilim, are be cut off. My identity is not important for that new part of my journey.

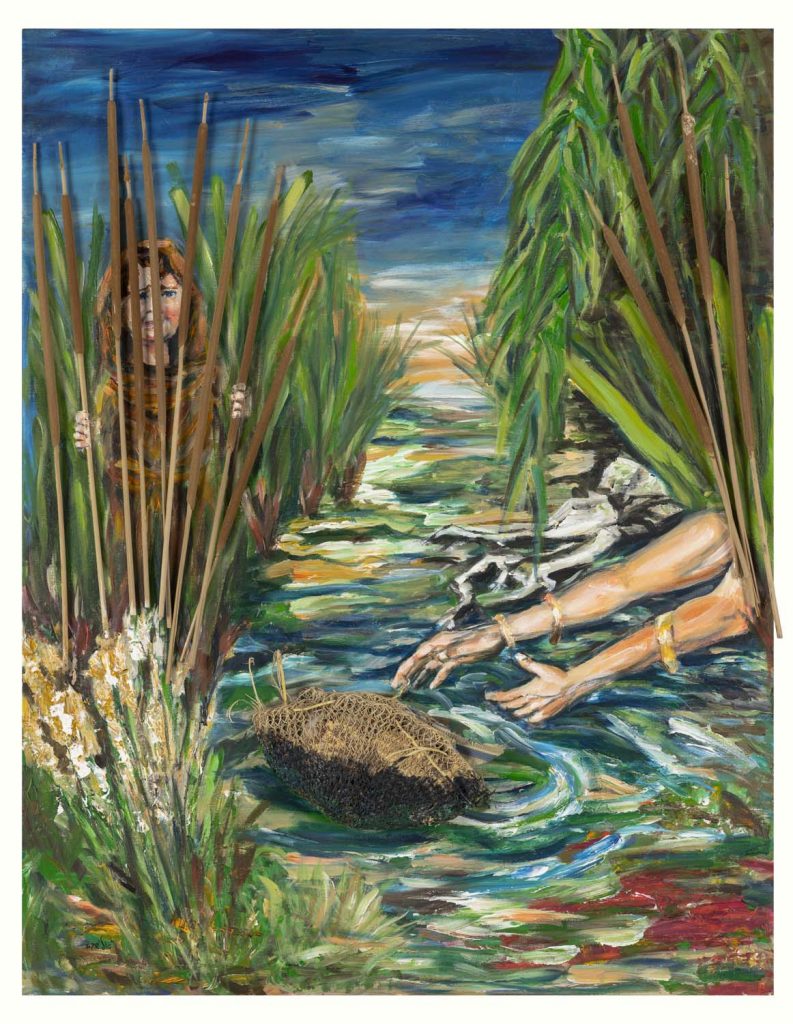

When first encountering the work of Elisheva Horowitz, I was struck by her use of textiles to tell us once again some of the best-known stories from the Tanach, our Bible. These stories were discussed around kitchen tables and in yeshiva study rooms across three millennia from Jerusalem to Kiev, from Yemen to Vilnius. Countless commentaries were written on them and they were the subject of many artists, both Jewish and Christian, including many who rose to worldwide fame.

Biblical stories are hardly a good place in which to strive for originality and yet Elisheva, with her startling use of textiles manages to do just that. The late great Israeli singer Arik Einstein sang about sitting on the water in San Francisco and “rinsing his eyes with the blues and the greens”. What was he rinsing them from? To any Israeli the answer is implied; the grays and the browns of Eretz Israel. Today, the Mediterranean Sea features strongly in the lives of many if not most Israelis, but in Biblical times our ancestors stayed mostly away from it, occupied as its coast was by malarial swamps and hostile Philistines. If they saw its blue waters at all, it was from the hills above Jerusalem, where the artist now resides, but only on those clear winter days and only as a distant mirage.

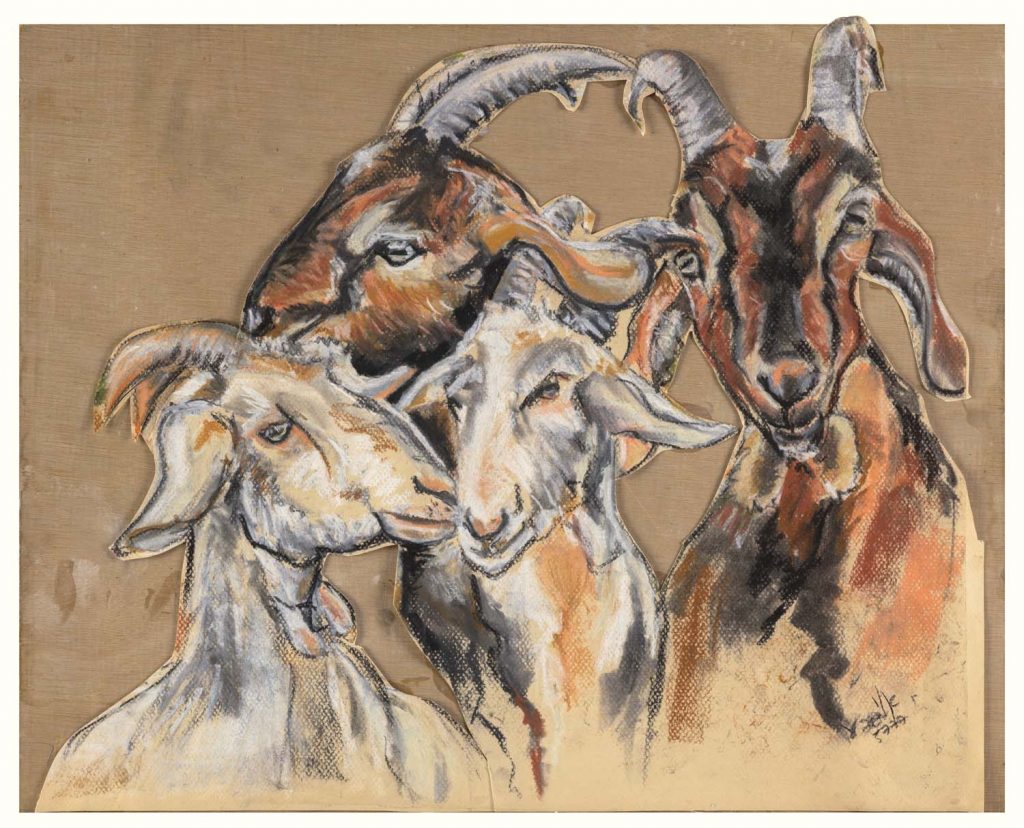

Apart from a brief spring, the landscape that surrounded them was full of saturated grays and browns, an infinite variety of them, all delineated in unflinching contrast by the merciless desert sun. Elisheva’s palette and her use of charcoal blacks to represent shadows and thus hint at the relentless sun that is ever present above us, takes me back to the time I had spent in my youth roaming the Negev and the Judean canyons, and the hills of Samaria.

Our land has always been a land of action, of decisive deeds by men and more often than not women who took their fates in their hands, grabbed them by the horns, and wrestled with them like Jacob wrestling with the Angel of the Lord to bend them to their will. If the Bible has a lesson and of course it has many, it is that nothing is impossible; that with will, ingenuity, and determination you can force your father in law to give you back what is rightfully yours or stop the all-powerful Persian emperor from exterminating your people.

Elisheva’s work brings us into the story, the action, by using body parts like the hands and the feet of the person who is moving, while focusing on the still subject of the movement. Her paintings are like the shots of a sports photographer who was clicking away as the player was sliding feet first into home plate. The cleats touch the bag, “safe!” yells the umpire, the deed is done. Like sports photographs, Elisheva’s paintings need context and that context is a familiarity with our history, our sources, our landscapes. For those of us who are so fortunate as to possess that context, much pleasure is derived from encountering her work and even more can be found in introducing it to the next generation.

You can do so yourself at the upcoming exhibition of Elisheva’s art at the Heichal Shlomo Museum at 58 King George Street in Jerusalem. The exhibition is entitled: “I Remember Your Name” (Psalms 119:55) and it is curated by Rachel Ziv. Gala opening is on Tuesday, May 21st, at 19:30.