Copyright: American Colony (Jerusalem). Photo Dept., photographer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

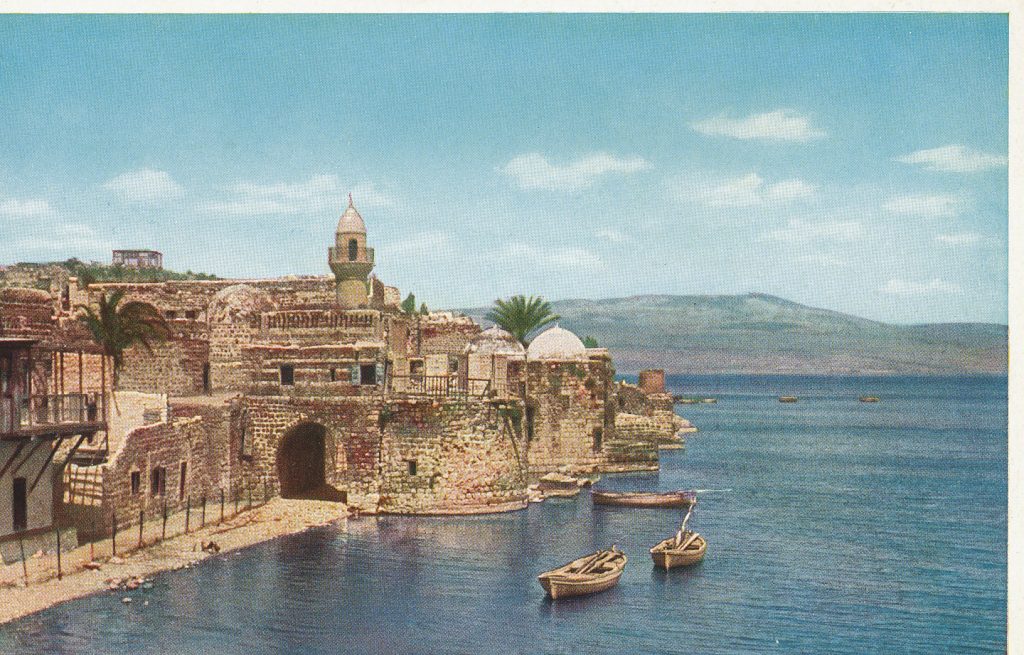

A few centuries ago when Israel was a province in the Ottoman Empire, a small mosque was built on the western shore of the Kinneret, the Sea of Galilee. The mosque was named Masgid al-Bakhri, the Mosque by the Sea, because when it was built, it was so close to the water line that the fishermen who fished the small fresh water lake could haul their boats on shore and find themselves at its doors, ready for prayers. The mosque was one of two in the backwater village of Tiberias, a city built almost exactly two millennia ago by the Roman emperor Tiberius to cater to visitors to the volcanic hot springs located just to its south, springs that were always thought to have healing properties and that still exist today.

Copyright: Bukvoed [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Copyright: צילום:ד”ר אבישי טייכר [CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5) or CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)]

After the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD, Tiberius became an important center for Jews in the Galilee and maintained its status as the fourth holy city for Jews in Israel for the next Millennium, well into the Arab conquest of the Near East. During that time Tiberius was the site of important innovations in Judaism, many of which, such as the phonology and pronunciation guidelines for the (by then no longer spoken) Hebrew language. Tiberias was the seat of the Masoretes, an influential group of Jewish scholars who preserved the tradition (hence their name, from the Hebrew ba’alei ha’masoret, masters of tradition) of ancient Hebrew pronunciation and coded it in the system of dots located under the 22 letters of the vowel-less Hebrew alphabet, called the Niqqud. To this day, the Tanach (the Hebrew Bible, substantially similar to the Old Testament) uses this system as does modern Hebrew, in poetry, for disambiguation of words that have different meaning, but identical spelling, and for foreign words and proper names, which would be difficult to pronounce without it. While the Tiberian pronunciation system does not precisely match how modern Hebrew is spoken, it is clearly the source for it, a source without which it would have been difficult if not impossible to preserve the language even as a language of prayer, let alone credibly and successfully revive it after nearly two millennia of disuse.

Copyright: Bukvoed [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

As the Jewish population in the Land of Israel dwindled together with its collapsing fortunes during the Byzantine, the early Muslim, and particularly the post-crusader Mamluk and Ottoman periods, so did the importance of the city of Tiberias. many left, but the city never completely lost its indigenous Jewish population. The deadly Fourth Crusade found Tiberias with 50 Jewish families and many ancient Torah scrolls. It was around that time, that the Egyptian-born physician and famed Torah commentator Maimonides came to the city and was buried there. During the early years of the Zionist movement, Tiberias had a mixed population of Muslim Arabs and pre-Zionist Jews, which made it a poor target for Zionist settlement activity. That changed in 1948, when during Israel’s War of Independence the Arab population fled fearing Jewish reprisals for years of hostility. The Tiberian Arabs fled never to return, fearing for their lives and believing the propaganda distributed by the Arab command encouraging the Arab population to leave so that they can return when the Jews have been defeated and ethnically cleansed. The outcome of that war was a different one and since 1948 Tiberias has been an almost exclusively Jewish city, with both of its mosques abandoned.

Copyright: Francis Frith [Public domain]

Copyright: Postcard: UVACHROM 6067 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Since 1948, for the first time in its long history, Tiberias, Tveriah in Hebrew, is a completely Jewish town with a population of over forty thousand and growing. It’s a popular tourist destination, located as it is on the shores of a fresh water lake and next to a hot-spring resort, but it is also, once again, a deeply religious city, with most of its residents belonging to the traditional and religious sectors of Israeli Jewry, many descending from Mizrahi and Sephardi communities.

Copyright: Team Venture [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

But back to our little mosque. Dropping water levels after drainage works performed in 1935 under the British Mandate left it somewhat removed from the shoreline and the lack of Muslim worshipers after the 1948 Arab exodus left it without purpose. In 1952, as part of the development of the city promenade on the street on which the mosque stood, it became the home of the Tiberias city museum, until that museum was closed in the mid-1980’s. Since then, for more than three decades, the mosque remained vacant and abandoned until just recently when Tiberias mayor Ron Kobi promised to rededicate the building as a city museum, enlisting for this purpose the local artist Ilana Gur. But, as it happens, these plans did not sit well with the powerful Arab leadership group in the towns and villages of nearby Lower Galilee. The Arab population in that region has experienced strong natural growth since Israel gained independence due to improved medical infrastructure and employment opportunities and they have become a powerful and sometimes militant voice in internal Israeli politics. Several prominent members of that group, including members of Knesset have visited the abandoned mosque and expressed the opinion that its reopening as a museum would hurt the feelings of Muslims in the region. The Muslim representatives met with the Mayor and set a date for further discussions. Hopefully, a solution can be found that will allow the Mosque by the Sea to become once again a place where people, this time Jews, Muslims, and Christians; Israelis and tourists, can visit and connect with the wonderful multi-cultural, multifaceted, and ancient history of Tiberias.