The seeds of destruction and exile were planted two centuries earlier when the Maccabees turned priesthood into monarchy

Copyright: Effib [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

“Latkes and sour cream” might be “peaches and cream” on the Hanuka holiday. However, metaphorically, it was not so for the Maccabean Kingdom after tfheir victory, which Jews celebrate for these eight days and nights. Many presume that Judah Maccabee and his three surviving Hasmonean brothers rode off into the sunset and their Second Temple Jewish Commonwealth lived happily ever after (until the Romans razed Jerusalem 200 years later and then crushed successive revolts). Alas, that was not the case. What was the true fate of Hasmonean Monarchy and why does it matter for us today?

If, as we shall see, the Maccabees’ successors embodied all of the evils that the prophets Gideon and Samuel warned would attend a Jewish monarchy, what does that mean for the celebration of Hanuka, our prayers for a messianic king, and the dysfunctional democracy of modern Israel?

Rancorous Israeli politics are a general symptom of the turmoil of our age. The West is watching as the post-war neo-liberal political order slowly dissolves and the frailty of secular democracies is increasingly evident worldwide. Globalism has ardent ideological detractors on the Right and Left, the Center is compromised by commercial interests, and the people are angry.

In the summer before the tumultuous 2016 election, my teacher, Dr. Barry Strauss cheekily suggested that America enter the British Commonwealth with William, Duke of Cambridge, as regent so that the election results would be merely for the office of our first prime minister. Might a similar concept work, in all seriousness, for modern Israel?

“Maccabee” or “sledgehammer” was the nom de guerre of both Judah of the priestly Aaronic Hashmonai clan and a term used to broadly describe the Jewish insurgency which he led with his four brothers against the Seleucid Empire and its Hellenist Jewish proxies. The apocryphal books of the Maccabees, as well as numerous accounts in the works of Josephus, Medieval Jewish Josephic texts, and midrashic sources, illustrate the bravery, audacity, and pure faith of the Hashmonai brothers in particular and their Maccabean forces in general.

They drew inspiration from the deathbed address of their zealous father and patriarch, Matityahu the son of Yohanan the High Priest. In the parting monologue preserved in the second chapter of 1 Maccabees as a preamble to the revolt, Matityahu appoints Judah to lead the Hashmonai clan and adjures his sons to be zealous for Torah Judaism like their direct ancestor Phinehas, whose murderous deed of valor punctuates Numbers 25 had been.

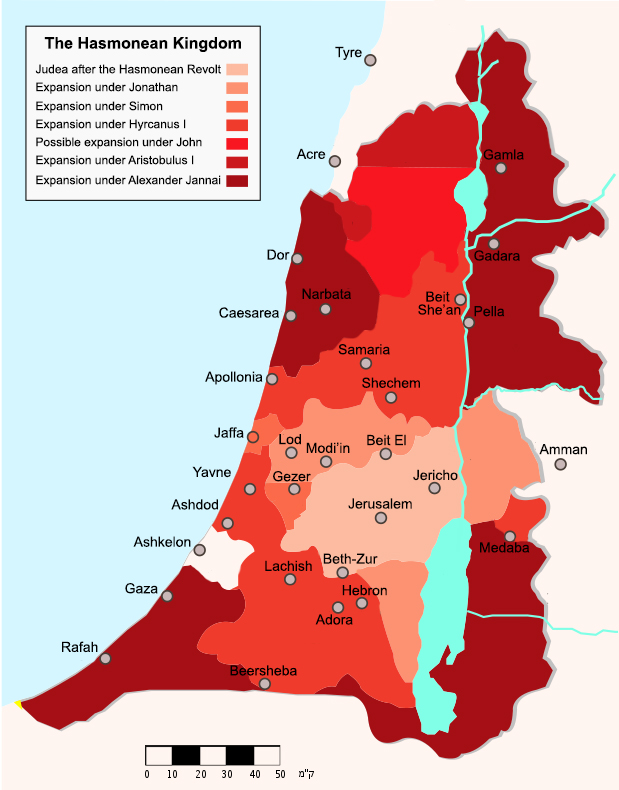

The Maccabees fought the good fight, reconquering Jerusalem at great cost, rededicating the Temple (literally: “hanuka”), Judaizing the Galilee and Idumea, and generally coercing a return to Torah observance among the Jews of Second Temple Judea. One Hasmonean brother, Elazar, was tragically felled outside modern Alon Shevut in the Maccabees’ failed bid to hold the strategically crucial Etzion highlands south of Jerusalem. He was crushed while dispatching a Seleucid war elephant which he mistook for one bearing a Seleucid royal.

This account and others are a staple of the Hanuka narrative, which is traditionally focused on the reclaiming of Torah, Temple, and territory. The menorah oil miracle testifies to the Divine Love which redeemed Judaism from disloyal Hellenist Jews. This Providence also favored the Maccabees in their asymmetrical conflict with vast Seleucid war machine, which inherited materiel and troop levies from the defeated empire of Achaemenid Persia. Amid all of the reclaiming and rededication, the Hasmoneans also claimed the otherwise vacant throne of the House of David, installing themselves as a ruling elite.

The problem was that the Hasmonean brothers and their children and grandchildren became hereditary monarchs in a Davidic fashion. This problem is obvious when we understand the checks and balances within the political structure of a Biblically observant Torah polity. The Mishna and Talmud Sanhedrin breaks it down for us: There is a high judiciary, the Sanhedrin of 71 rabbinical sages, which oversees a system of lower courts, each of 23 sages in cities throughout the Land of Israel. The Sanhedrin confirms both lower court judicial nominees as well as a qualified Jewish king from the House of David. That kingship is an executive branch which must have the consent of the Sanhedrin high court to wage wars or make ‘capital’ expansions of Jerusalem. To keep power in check, Kings must be Davidic and may not sit on the Sanhedrin.

Finally, there is a third branch of power centered in the Holy Jewish Temple. At its pinnacle there is a high priest who must be a hereditary Aaronic descendent and one who is the spiritual leader of the nation. This office must effectively pilot a vast enterprise which facilitates a metaphysical union of Divine Energy with an earthly edifice while maintaining extensive property, functioning as a financial institution managing a complex sacrificial schedule, and providing pastoral leadership in diverse arenas too many to list here. The high priesthood, like the throne, is ordinarily a hereditary office. However, for high crimes, both answer to the Sanhedrin who may judge them.

Now, the problem of the Maccabees becomes clear: the two branches of the royal executive and the high priesthood were effectively merged, either in the same person, or within the charm circle or nuclear family of the Hasmonean clan. The great medieval rabbi Moses ben Nachman outlines this obvious problem within his commentary on the end of Genesis as regards the prophetic bestowal of executive power upon the Tribe of Judah and its scions of the House of David. He assembles a force of Biblical verses and expositions from both Talmuds as he demonstrates that not only must a Jewish king be positively a Judahite with David lineage, but a king may not be from the Aaronic priesthood.

We do not need Lord Acton to know that “absolute power corrupts absolutely” and that the descendants of Phinehas and Matityahu would sacrifice their souls in the process of building their own Jewish monarchy. Kabbalists understand that the soul of an Aaronic descendent is unfit for royal power. Throughout the Holy Zohar, we learn that souls of priesthood are pipelines built to manifest Divine Lovingkindness in both sacrificial and ritual duties as well as in Torah education. This equips them for sporadic zealotry to these ends, but not for a productive use of sustained political or judicial power.

Kohanic Priests’ inherent capacity for expansive God-consciousness will be perversely misdirected and lead them horribly astray if they attempt to channel their talents into war, economic policy, and statecraft. Zealotry has its season, which fades with the need for social stability and political structure. Recall that this relates to King David himself, whose warfare was a disqualifying factor for his involvement in completing the Holy Temple in Jerusalem.

Rabbinical literature is rife with sordid tales of the 200 years of Hasmonean reign which detail the sale of the office of high priesthood to wicked and unworthy royals who made larcenous use of their power and influence. Profligate Hasmonean heirs squandered wealth, killed enemies, and led the state into decline. They could not, or would not, be judged by the Sanhedrin and competitors for the throne certainly did not ask this high court for permission to wage civil wars.

In one such conflict, the two warring Hasmonean contenders were brothers. One called in a favor from an old Maccabean ally from the days of the revolt, the Roman Republic. The emerging Mediterranean superpower had recently conquered much of Greece and was eager to help a Hasmonean royal secure the throne. After a bitter civil war that culminated with a harsh siege of Jerusalem, the Romans’ Hasmonean client won and their role as referee in Judea was cemented.

Over decades, the Romans leveraged their power, making successive Hasmonean kings their vassals. Those kings increasingly polluted their Aaron lineage, disqualifying themselves for priesthood, and found themselves as altogether questionably Jewish as they managed an eastern marcher province for Rome. The quasi-Jewish King Herod epitomized these latter members of the House of Hashmonai. Herod executed much of the Sanhedrin and built lavish public works to endear himself with the bitter Judean public whom he feared enough for him to also construct fortress palaces for his escape in the event of revolt.

“…In those days, in this time,” concludes a blessing we say upon lighting our Hanuka menorahs. In our time, the problem of legitimacy looms over the success of the modern Jewish commonwealth. Many are wont to compare the illegitimate Aaronic kings of the Maccabean kingdom to the decidedly non-Davidic parliamentary democracy of modern Judea. The crass neglect of Torah Judaism by so many modern Jews sets the establishment of the State of Israel at odds with Hasmonean Hanuka. Is there a way to bridge the political gap between the Second Temple priest kings and the scepter of Judah, and the structural gulf between the Knesset and the House of David?

One recent approach is in line with Dr. Strauss’ modest proposal, though it might seem regressive or antiquated, but certainly as effective as Israeli coalition politics in the recent year: a Davidic monarchy. By this, I refer to the prescription of parliamentary monarchy written by philosopher Michael Wyschogrod in a May 2010 monograph published in First Things. He concludes:

“The solution that I propose is by no means unusual for a constitutional monarchy. It is a common occurrence in monarchy that no king is present or that the present king cannot rule, for example, due to youth. In such situations, a regent is appointed as a placeholder for a king. Such a placeholder can either be appointed or elected. A regent safeguarding the Throne of David until such time that divine intervention identifies the rightful heir to the Davidic kingdom would thus assume the functions now performed by Israel’s president, the symbolic head of state.”

His agenda is to re-inaugurate a moral bearing for the Zionist project rooted in the culture of the Jewish ethnos. He explains this reformulation of Israeli democracy as a reconciliation of Torah Judaism with Zionism and recalibration of Jewish identity:

“This action would build into the self-understanding of the state of Israel the messianic hope of the Jewish people, while excluding a messianic interpretation of the present state of Israel.”

Wyschograd’s provocative formulation clarifies the political role of a Davidic Jewish king. In doing so, the role of Torah and tradition is clarified so that the Maccabean victories may be effectively contrasted with Hasmonean corruption as a means to rededicate the Jewish state to ideals older than democracy and which pertain to the soul and vitality of a nation. This embodies a nascent form of ‘teshuva’ in which a return to the values of the Torah is also a step forward for the rededication of the Jews to their land.

2 comments

BINGO, very nice article, nor do we need Lord Acton to understand that players are on the field. The behavior of the “conduit” zealous propensities, resides in America. considering the adding of their Sovereignty as also the conduit. The proposal seems sound in construct. Israel is “blind in part” but not totally blind. The queen of England stated small steps, but leaps are being made. Mercy is a most powerful thing, required for Israel’s return being favored by the Creator. Thanks for watching so closely, I like to “watch” very closely myself. GB and SF

Rabbi Yosef and I thank you for your kind words