I have always felt that photography was the most challenging of all artistic media. Perversely perhaps, I feel that way because photography does not require virtuosity, but does require a concrete, tangible subject. Not to belittle photographers’ skill with their favorite cameras, but I doubt that anyone has ever said that ten thousand hours practice with a Leica make you just barely good enough to use it reasonably well. And yet, that is the case with musical instruments as well as marble or canvass.

Musicians, painters, sculptors, and even cooks, can hide a moment of unoriginality, a creatively bad day behind their virtuoso control of their chosen medium. We can see this in a few of August Rodin’s sculptures and in many Peter Paul Rubens’ paintings that festoon the walls of every art museum in every medium size city in Europe. We can taste it in some of the items on a chef’s tasting menu in a fancy restaurant. We can feel it, we are aware of it and yet we still enjoy the offering simply because it is so well made. The sheer skill involved in its production becomes an end in and of itself and we do not feel cheated by the experience.

And then there is the subject. Many sculptures and paintings simply don’t have one, which is precisely the point of abstract art. These works tell us something about the artist, making them, in a deep sense, self-portraits, conveying nothing of the world outside.

Photography is different. A great photograph is a dialogue between the photographer and his subject; it is a road map for us, the viewer. It is an invitation to see the subject of the photograph in a different way, a specific way, the way that the photographer saw it when the shutter blinked open. It requires, I feel, a very certain type of personality to take great photographs precisely because the artist is so obscured by both the subject of the photograph and the lack of necessity to exercise great skill in taking it.

Perhaps there is a reason why there are no child prodigy photographers like there are musicians. A personality not yet developed, a life story that is yet a blank page cannot guide us, cannot draw us, cannot show us the way to the true meaning of the contents of a photograph.

Perhaps the true virtuosity of a great photographer, his ten thousand hours of practice, is his own life journey, a journey that he uses to punch his ticket, to buy the rights, to obtain the street cred he needs to tell us: “follow me, guys, let me show you what is really here!”

Sarah L. Singer’s life story is a photographer’s life story and a Jewish life story, too. Her background as a painter, her journey from the modern to the traditional, her travels that took her from exile in America back home to Israel, they can all be seen in her work. Her experience in Africa comes out clearly in her photographs, which are like visual gut punches with never a blurry line, never a soft contour, always unflinching, direct, primal.

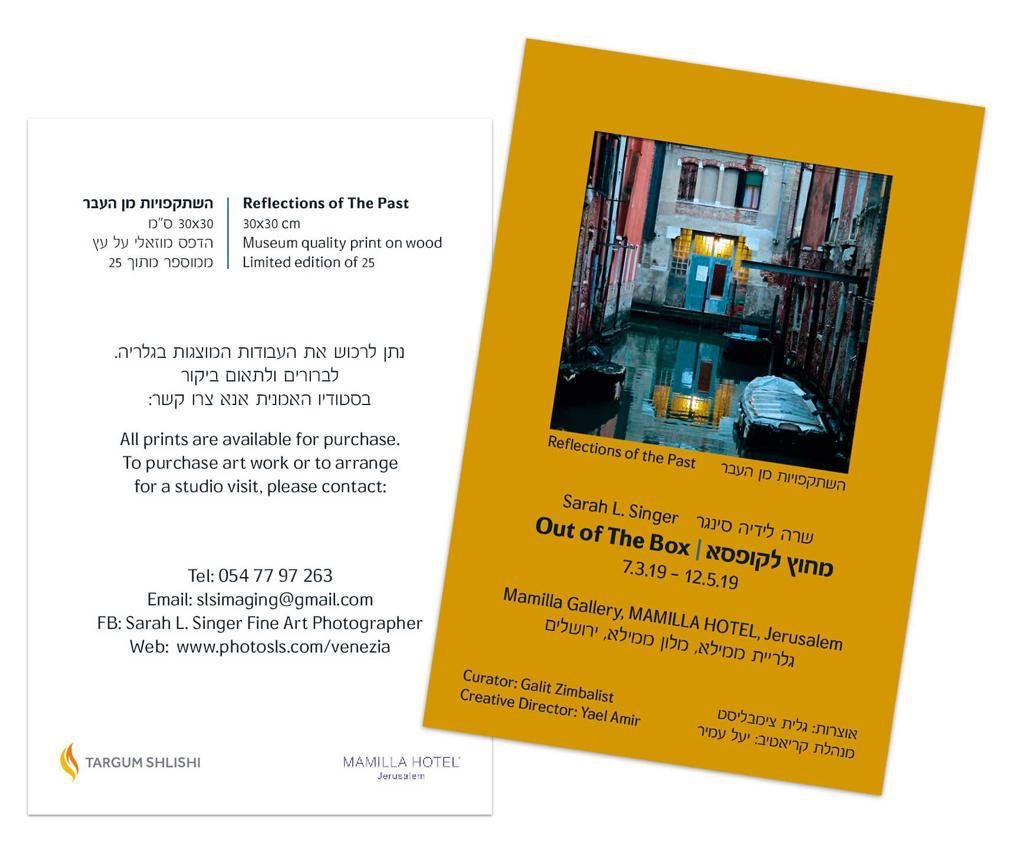

The exhibition of her works that is currently taking place in the swanky Mamilla hotel in Jerusalem is a photographic essay of the old Jewish ghetto in Venice and it would be difficult to imagine a more fitting and at once challenging subject. Italy was the first stop for Judean exiles in the aftermath of the failed Great Revolt of 70 AD and Bar Kokhba revolt half a century later. As these Judeans moved on to France and Germany and finally Eastern Europe, other Jews from North Africa and Spain took their place. In Venice, Florence, Sienna, there are the ghost neighborhoods they had left behind with their impossibly narrow streets and sometimes an erstwhile synagogue, now a museum. The centuries-old buildings remain, but the Jews are all gone with nothing but ghosts and name plaques left in their old homes and synagogues.

As a Jew, the feeling one gets when visiting these places, when hearing the stories how once every few decades the Jews were herded out of the ghetto to be burned alive in the town square because the well water ran dry or because Napoleon’s armies wreaked havoc on the town is hard to describe. It is joy, yes, joy, that these kinds of things will never happen again, but also sadness that these Jews, our forefathers and mothers are long gone, that they lived lives so full of suffering and uncertainty, that there is so little of them that remains in these places.

Sarah’s photographs of the Venetian ghetto do justice to these feelings more than my words ever can. The one thing that is impossible to miss is that they are empty of any living thing. Only in one photograph, a kestrel is in sharp focus flying across an impossibly blue sky. The life force of the kestrel is the negative of the lifeless, bare tree, a tree that gives no shade to the little ghetto square with its communal well. Which is just as well, because the denizens of the ghetto are no longer in need of shade or water. They have flown away, never to return.

Details of Sarah’s exhibition are below: