In one of the more amazing turns that my life has lately taken, I find myself blogging about Israeli plastic artists on the website I edit, Tsionizm.com. In that endeavor, I often find myself secretly hoping that the artist I write about is somewhat less than a virtuoso in their craft. I wish that the key aspect of their artistic expression lies not in their mastery of their chosen medium, but rather in the concept, the drama, the intellectual prowess, the historical references and Biblical allusions.

It is an admittedly selfish desire because it gives me something to write about, it provides ample fodder for my ruminations, my idle musings. Artists who rely on the sheer mastery of their chosen media leave me at a loss for words because they have already said it all in their work, work that requires neither explanation nor elucidation from anyone, your humble servant included.

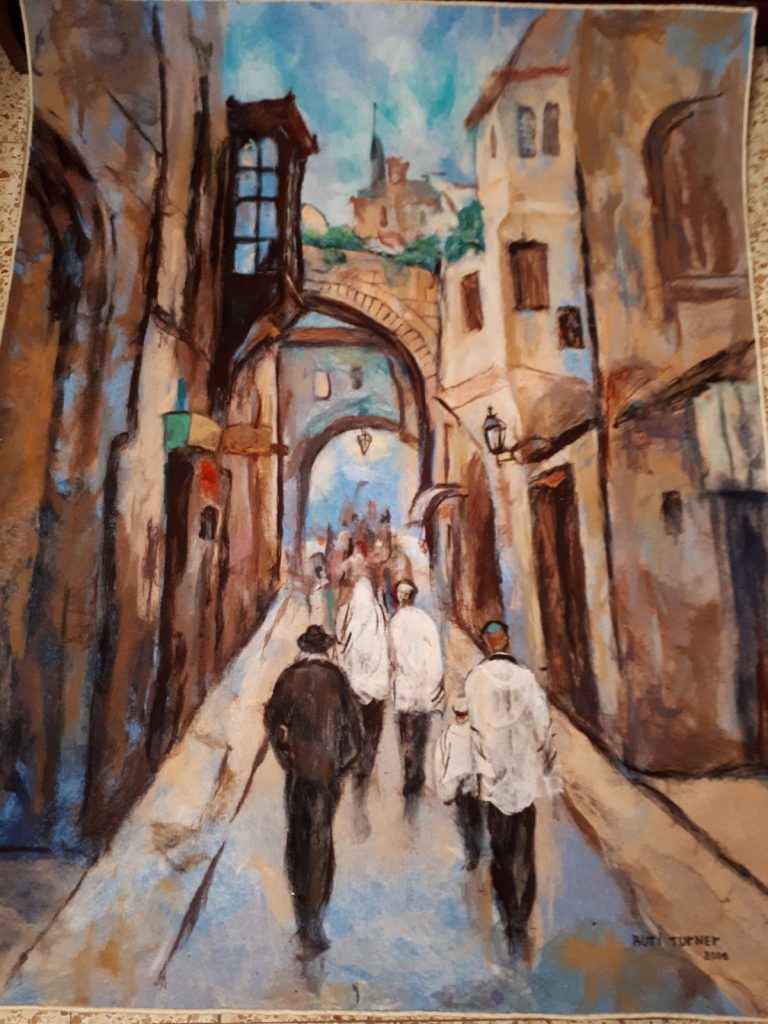

The Israeli artist of Georgian background Ruthie Turner (Rosodan Tenorishvili) falls into this category. Her mastery of weaving is such that it creates a cognitive dissonance. On one hand, her depictions of scenes from the Old City of Zfat (Safed), her stylized still art of judaica pieces or her renderings of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Schneerson seem not very different than those that can be found in galleries that cater to international tourists in most Israeli cities and towns. But then one realizes that these are not oils, gouaches, or watercolors; these are tapestries, weavings, rugs, so exquisitely made that they fool the eye into believing that they are something else entirely.

Often, the object of representational art is making something that is inherently two-dimensional appear three dimensional. An entire branch of science, developed by the early Dutch masters in the 15th and 16th centuries was dedicated to thus fooling our senses. There were trade secrets that were closely guarded, bitter rivalries among practitioners, the entire suite of attributes of any high technology.

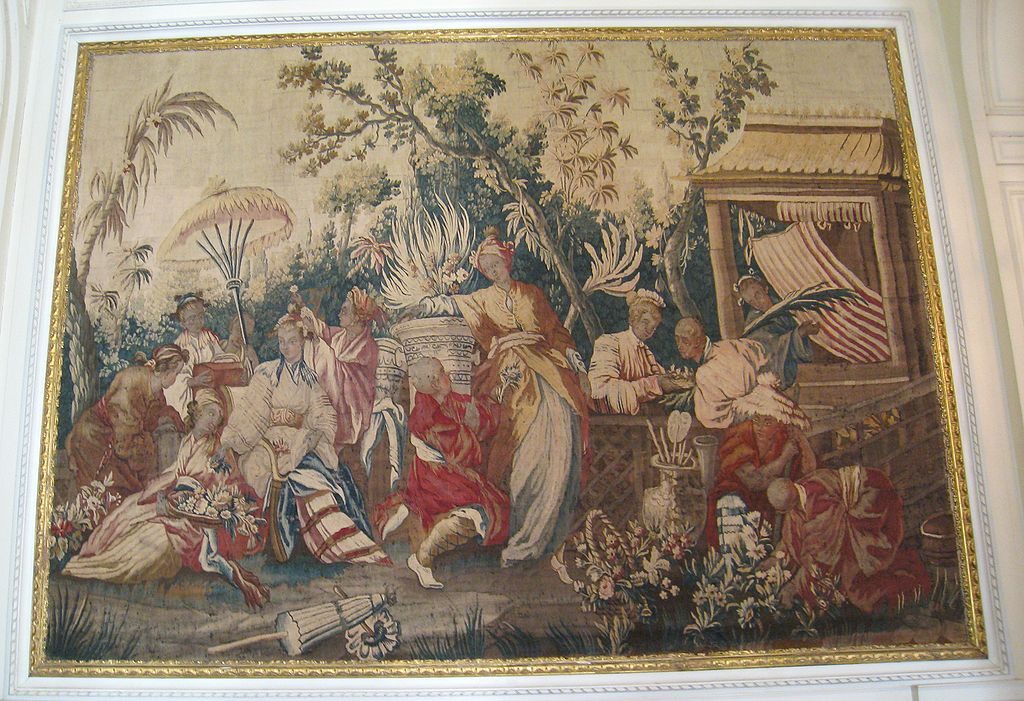

Ruthie’s work has the opposite effect; it uses a three-dimensional medium and fools us into thinking that we are looking at a rather naively executed two-dimensional painting. In this Ruthie appears to be rather unique; tellingly, the great tapestries of the Gobelin school produced in early to late Renaissance Belgium did not attempt to evoke such an effect or use the contemporary perspective techniques that were so common among the painters of that age. Rather, they were content to let the medium, the yarn itself, provide that missing third dimension, rendering with it scenes that were almost intentionally flat, flouting the rules of perspective by their very design.

Great art is a bridge; it takes us on a journey from the past to the present and to the future, it makes us remember places we have visited and think of where we might want to go next. This is what Ruthie’s tapestries do to me, but you can judge for yourself at her solo exhibition running through July 28th at the Heichal Shlomo Museum on 58 King George Street in Jerusalem.