A retrospective of the works of Naftali Solomon a member of one of Israel’s founding families and a wonderfully Jewish artist is now taking place in the “Mother of Settlements”, Petah Tikvah

I must admit to a fair amount of trepidation in setting out to write this piece. Its subject is art, but it is the artist’s identity that is giving me pause. If Israel had a founding aristocracy, the Solomon family would surely be among its charter members. Yoel Moshe, Naftali’s grandfather was among the small group of people who braved malaria and hostile Arab neighbors to leave the relative safety of Old City Jerusalem and establish Petah Tikvah, now a thriving city of nearly a quarter million, then half orange grove half malarial swamp. No one in Israel is unfamiliar with the late Arik Einstein’s beloved ballad about the founding of Petah Tikvah, really the founding of the modern state of Israel, in which Yoel Moshe Solomon figures so prominently. What can I say, I am humming it in my head as I write these lines.

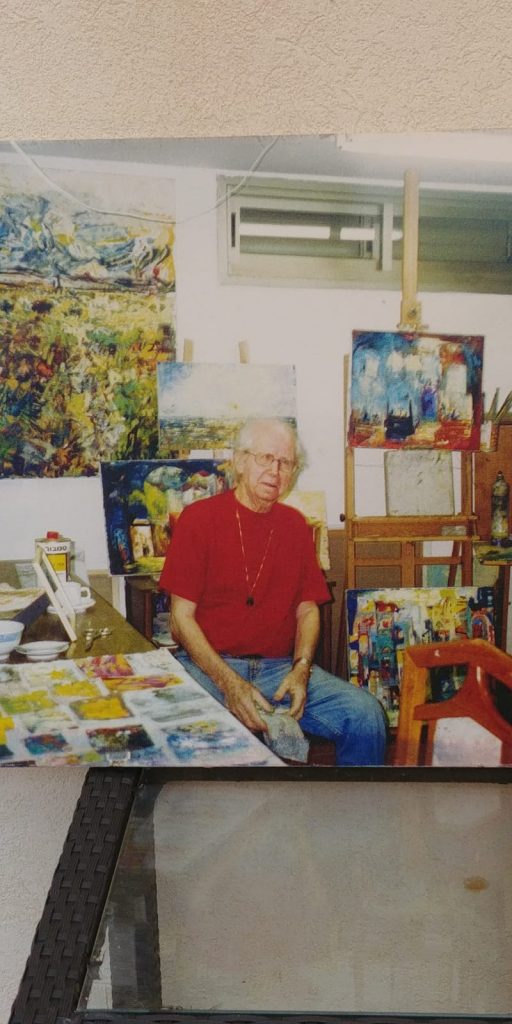

Naftali has passed on now, but his daughter Nitzah still maintains the old house in Petah Tikvah and the artist’s works are now presented in the Blue Bird Gallery at 75 Rothschild Street in that same city. It was Rothschild’s money that paid for draining the swamp and making the low-lying parts of the town livable, so it is fitting that Naftali’s paintings, the retrospective of his life’s work is presented there.

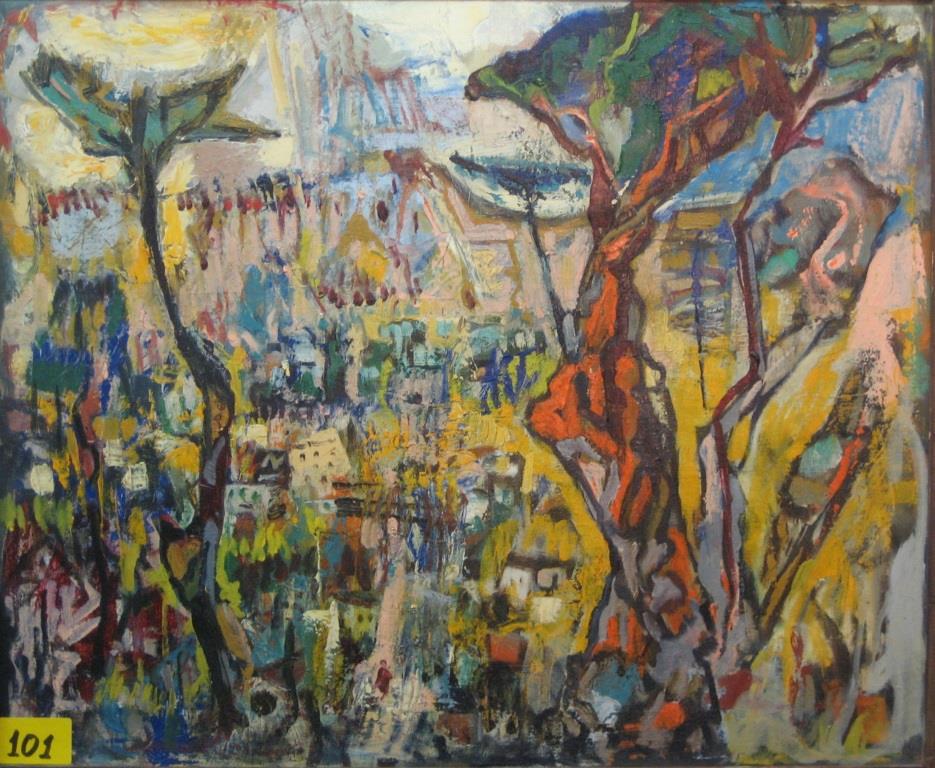

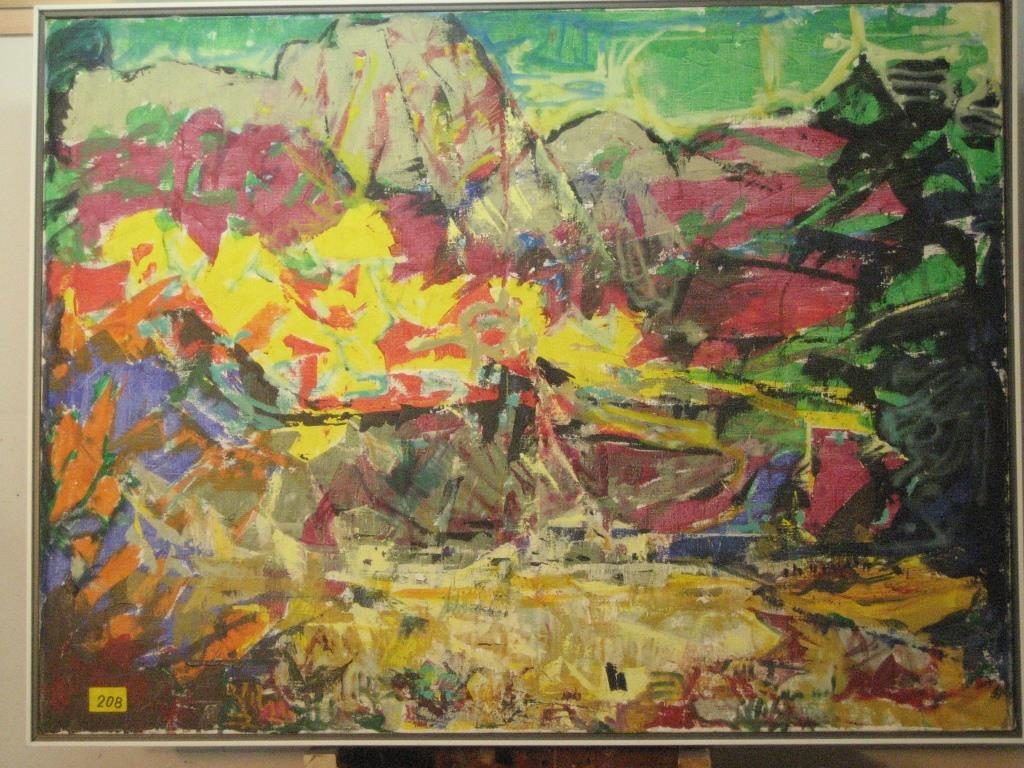

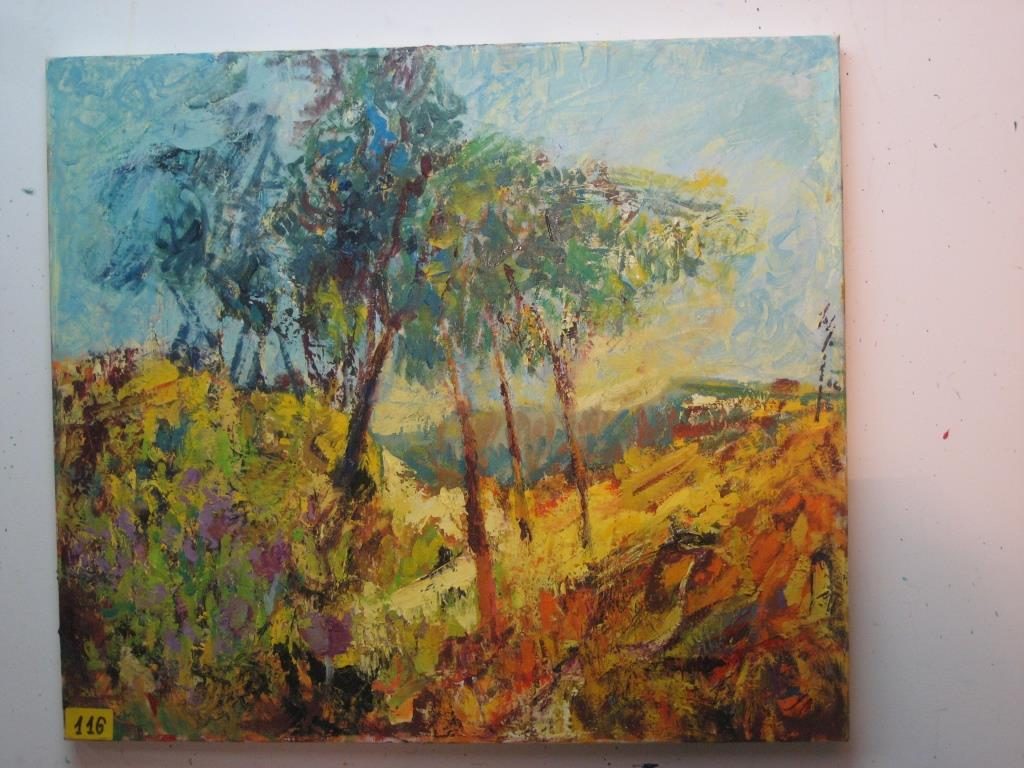

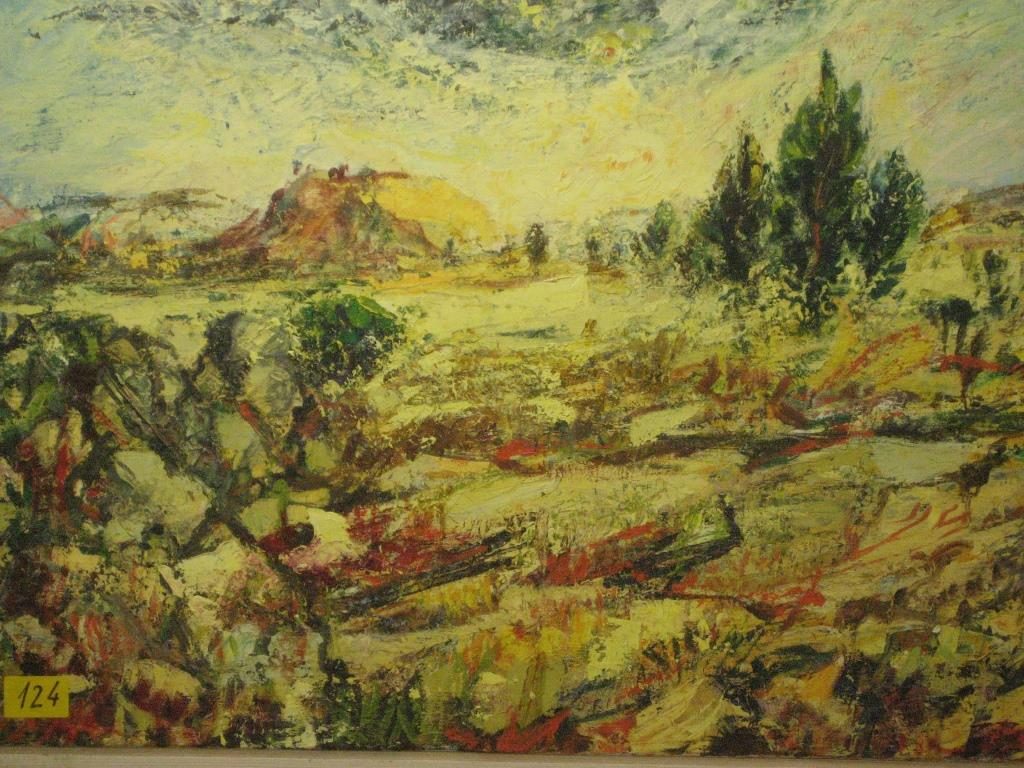

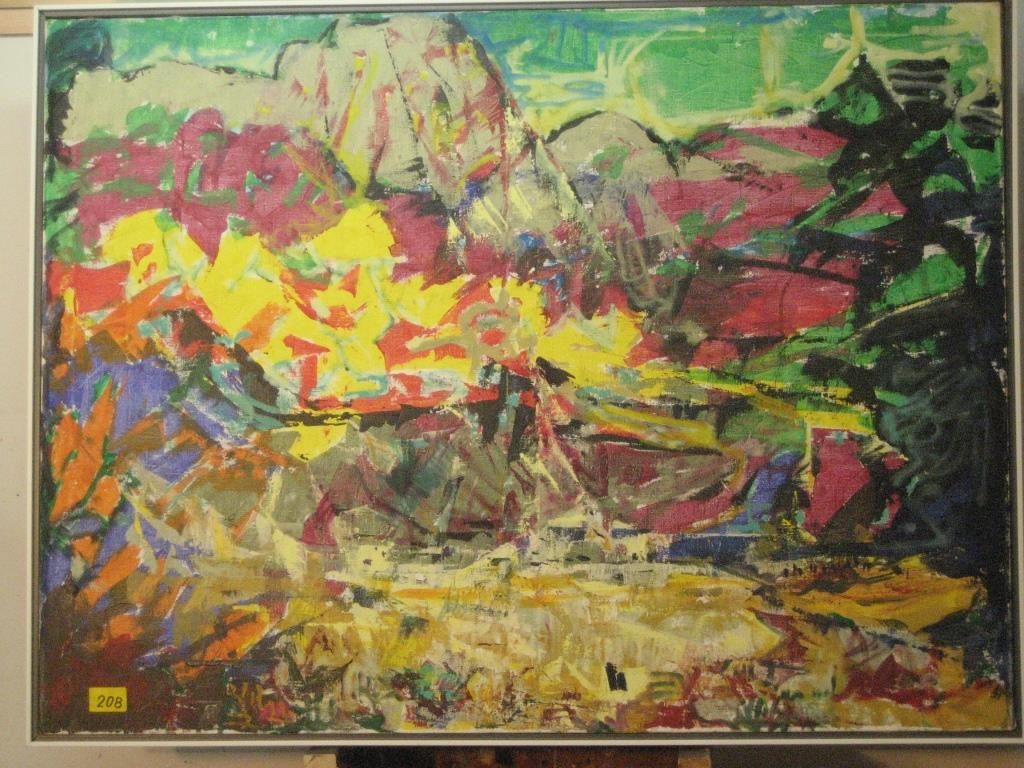

Naftali bridles at being pegged as primarily a landscape artist, making sure that we pay attention to his sketches and oils on subjects as varied as female nudes and biblical tales, and yet he always seems to come back to the landscapes of Eretz Israel, the Holy Land. These landscapes seem to have been burned into his retinas by the merciless Israeli sun, never to be erased, no matter how much the artist may perhaps have wished them to be.

Israeli landscapes are not the easiest to paint. There is no green lushness of Northern Europe, no Tuscan vistas. There is drama, but it is hidden from all but the most discerning viewer. One must look for it in a small cluster of eucalyptus trees brought from Australia around the time of the founding of Petah Tikvah to help drain the swamps on the coastal plain and in the low-lying areas around the Sea of Galilee. It can be found in a patch of red poppies, their explosion of color marking the end of the brief Israeli winter and the start of the long and arid summer. There is a smallness in Israeli landscapes that reminds me of how my grandmother used to address God with whom she often had the bitterest of arguments. “Gottenyu” she called Him in Yiddish: “Little God”, “Baby God”, even. It is a term of endearment not familiarity, love not condescension.

There is a tension in Naftali’s landscapes, an attempt to enlarge the unenlargeable. “You have to be bigger, bolder,” he seems to be yelling at the hills, the trees, the sky; “you have to give me more!” His use of thick brush strokes and bold colors is tantamount to grabbing the modest Israeli vistas by their lapels and rather rudely shaking them. There is no caress, like in Van Gogh’s Province paintings; but there is love and infinite familiarity and in the end, acquiescence.

Naftali grew up in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family, but in his later life he became an avowed atheist, seeing in the Bible nothing but a collection of myths. Jews have always, ever since Abraham, had a contentious and adversarial relationship with Him. It is history’s quintessential love-hate relationship, the one between the Jews and our God. He can certainly dish it out, our Gottenyu, but so can we, and from this struggle, one that spans most of civilized history, an amazing outpouring of creativity has emerged, one without which human history can hardly be imagined. Naftali’s paintings, his raw landscapes, all but pornographic nudes, and even his cockfight scenes in which he rails against the futility of war, are all a polemic with the God he had abandoned, the One he didn’t believe in, but without whom there would be nothing to paint and nobody to fight with.

Naftali Solomon’s retrospective is being held at the Blue Bird Gallery, 75 Rothschild Street, Petah Tikvah and it is curated by Sarah Raz, the chairwoman of the Petah Tikvah artists association. The exhibition runs through May 5th.

For Hebrew speakers and those simply wishing to see more of the artist’s work, there is a wonderful video interview that can be seen here: