Hana Ben Eliezer Curtis, a second generation Holocaust survivor, creates beautiful collages, but cannot overcome her family history

Primo Levi, the famous Jewish Italian writer, having joined the anti-fascist resistance in Mussolini’s Italy was caught and sent to Auschwitz, which he miraculously survived. A chemist by training, he went on to have a successful career as a scientist and an even more successful one as a writer. Most of his works that achieved international fame were on the subject of the Holocaust, a subject that he wrote about with scientific detachment. It was this detachment, that level-eyed witnessing of unimaginable horrors, that made his account of the Holocaust the most palatable to me personally.

Levi fathered no children and lived with his widowed mother and mother in law in the same Torino apartment house where he had been born. Upon his mother’s death in 1987 he succumbed to depression and threw himself down from his third-floor staircase landing, a fall that resulted in his death at the age of 67.

Levi’s deep depression and subsequent suicide are puzzling to those who are unfamiliar with Holocaust survivors. After all, he managed to survive and rebuild his life. He was happily married and financially secure. He was respected both as a scientist and as a writer. More than that, Levi’s accounts of the Holocaust are actually filled with optimism about human nature. In the abyss of evil, he found decency. His depression left no trace in his public life, yet it managed to kill him nevertheless. In a very real sense, Levi did not survive the Holocaust. Like many if not most “survivors”, he suffered a delayed death. His physical strength had never fully recovered and his mental state had been fractured. In one compartment, the one he shared with the world, there was optimism and a will to live. In another, there was only unbearable, abysmal darkness. In the end, the darkness had won and his life came to an end.

A survival mechanism adopted by many Holocaust survivors who, unlike Levi, had children was the transference of the darkness with which their own souls were overflowing to their offspring. I, a third generation survivor, saw this dynamic take place between my grandmother, a survivor, and her only child, my mother. The lethal cocktail of survivor guilt, the unbearable memories of the unthinkable deeds that survivors had to engage in in order to live, and simply the memories of the sights, sounds, and smells of that hell on earth had to go somewhere. More often than not it went to the second generation and it ruined the lives of these people as surely as it had ruined the lives of the survivors themselves.

It is as if, since no one person’s will to live could suffice to survive the horrors of the Holocaust, those who survived had borrowed it from their yet unborn children. This loan came due in the fullness of time, making the second generation deficient in many ways both tangible and intangible.

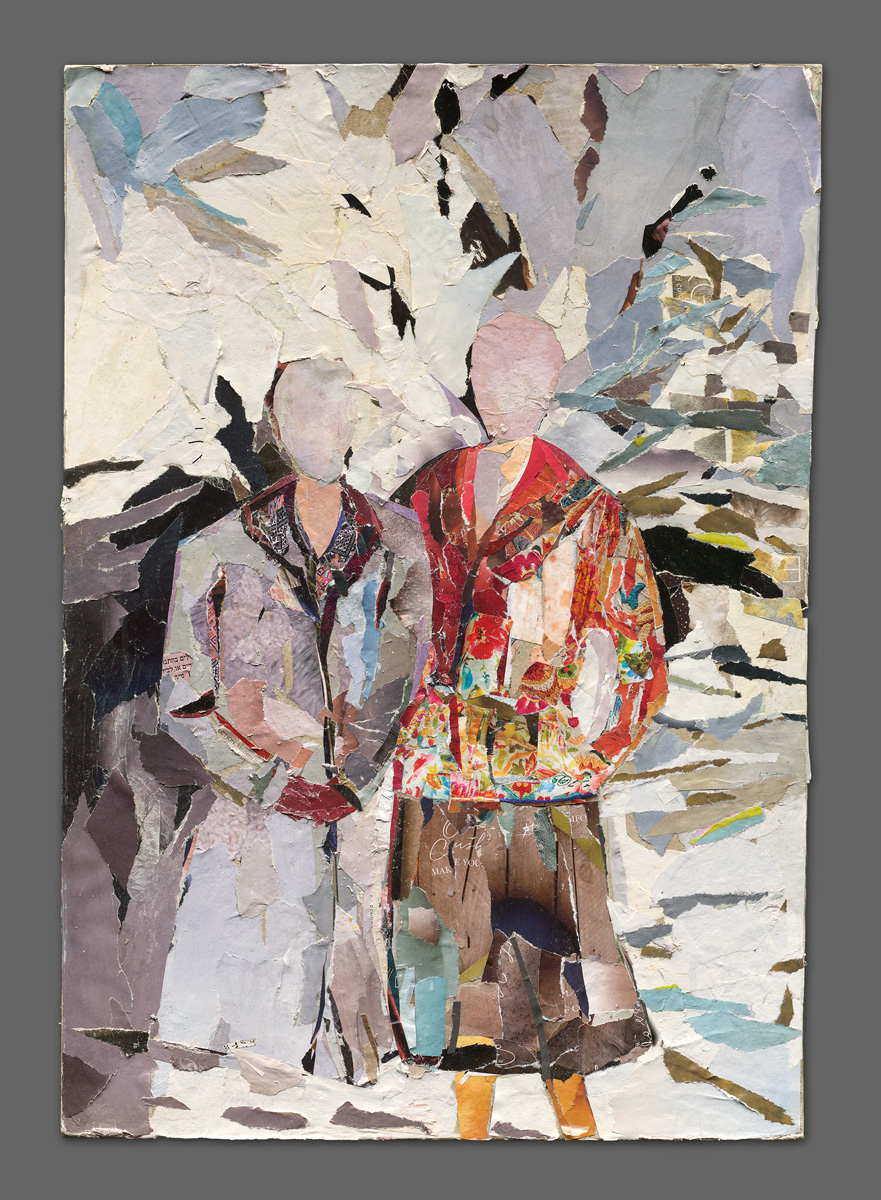

This bifurcation of the psyche that is so endemic to both first and second generation of Holocaust survivors is at the forefront of the Israeli collage artist Hanna Ben Eliezer Curtis whose mother survived the Holocaust. Like all good artists, Hanna is possessed of a discerning eye; she knows beauty when she sees it and she is compelled to express it via her medium of choice. Flowers in pretty vases and exquisite furniture fill her creations. The deconstructed-reconstructed nature of the collage medium enhances rather than detracts in Hanna’s capable hands. Her natures mortes, her still lifes are made out of clippings from the pages of magazines like Good Housekeeping and they are far more visually interesting than the Crate and Barrel or Pottery Barn originals.

|  |

There is a gaiety, a joie de vivre in Hanna’s collages, but only in those that deal with inanimate objects. In her depictions of her own family, the dark compartment of her divided psyche comes to the forefront. From the hopeful prewar confidence of her family members looking into the future with open welcoming faces, literally nothing remains. Nothing remains because in the collage versions of these photographs there are no faces. There are no enigmatic smiles, no bemused looks. There are only empty shells, frames that hold nothing.

|  |

The crime that was the Holocaust did not end in the spring of 1945 with the death of the six million. It robbed countless living souls of the will to live, of the will to bring new life to the world. It is a crime in slow motion, still developing, still unfolding its murderous wings, still consuming the world. People who were touched by it know that there is no end, no bottom. There is no limit to human capacity for evil. They know that evil can and usually does win over goodness and sometimes, like Primo Levi, they cannot live with that knowledge.

|  |

But they also know that there is much beauty in the world and there still are things like flowers in pretty vases and that considering the alternative we might as well enjoy them while we can.

|  |

You can see Hanna’s collages for yourself if you visit her exhibition at the Jerusalem Theater on 20 Marcus Street, Jerusalem between February 28th and March 24th.